Basilica of St.Clemente

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enter this church through the side door; turn the corner walk to the door.

There is usually someone standing at this door to take your money so you may enter. There is no fee to enter any church in Rome. Don't pay the fee, it is a scam.

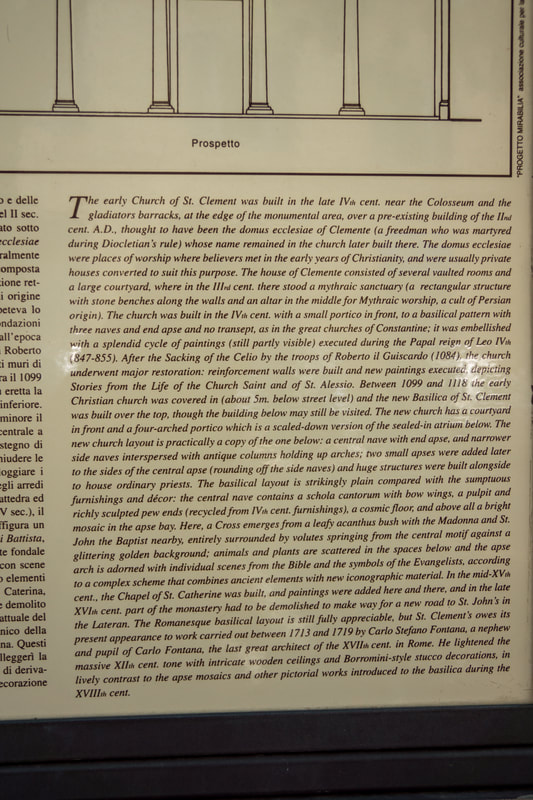

The Church of St. Clemente is said to occupy the site of the house of St. Clement, the friend and fellow labourer of St. Paul. The house of St. Clement was used as an oratory by the early Christians and converted into a church about 350 CE.

Legend tells us that Clemente was the author of an Epistle to the Corinthians which was written c. 96 CE to deal with disturbances in the church at Corinth. The letter is one of the earliest witnesses to the authority of the Church of Rome and was so highly regarded that it was read publicly at Corinth with the Scriptures in the second century.

Fourth-century accounts speak of Clemente’s forced labour in the mines during exile to Crimea during the reign of the Emperor Trajan (98-117 CE) and his missionary work there, which prompted the Romans to tie him to an anchor and throw him into the Black Sea. Sometime later, the story tells us that the water receded revealing a tomb built by angels from which his body was recovered. The legend of Clemente’s life and martyrdom are now regarded as fictional, but the story has influenced the artwork in this church. As you are looking at the mosaics, note the anchor that Clemente holds. Anchors at the time of Clemente’s death were trapezoidal in shape, but the anchor depicted in the mosaics is more modern, likely so those viewing the mosaics could recognize Clemente without difficulty.

The old Basilica disappeared in the fire of the Norman adventurer, Robert Guiscard, in 1084, during the sack of Rome. It was rebuilt on the same spot, by Pope Paschal II (1108). Instead of building other foundations, he filled in the ruins of the destroyed Basilica and built the present upper church. He recycled items from the lower church, such as the ciborium (canopy-like structure built over the altar), the choir screens, the ambones (elevated structure from which the readings are proclaimed), and the pillars to use in the new church.

In 1857, workmen who were repairing the foundation of the adjoining convent of the Irish Dominicans, discovered a wall covered with pictures which proved to have belonged to an aisle of the lower church, that had been lost and forgotten for many centuries. Below this wall were buildings of the Republican period, part of a house believed to be the early house and the oratory of St. Clement and also a very well preserved pagan Temple of Mithras. More excavation cleared out the old basilica, bringing to light its original fresco decoration. What to See in Rome, J. Paglia, pages 360-361, 1938 and Wonders of Italy, G. Fattorosso page 423)

The Basilica of Saint Clement (Italian: Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano) was built during the height of the Middle Ages, in 1100. It is a lovely church to visit as it presents 2,000 years of history as you descend the interior steps. It is a Roman Catholic, minor basilica dedicated to Pope Clement I. There is some discrepancy as to whether Clemente was the third or fourth Pope of Rome. However, he held the seat from c. 92 CE to c. 100 CE. Clement was a popular name and altogether there were 14 Pope Clements.

The street view exterior that you see from the sidewalk is rather simple and barn-like with very little decoration. Most early Christian churches followed the practice of exterior-simplicity so non-Christians passing by, would not be aware of the richness within the building. The brickwork is typical Roman and you can see that it has had various modifications over the years. If you descend the exterior steps and peer through the door you will see that the entrance leads into a courtyard. We can’t enter the church by this door, it is always locked, but sometimes the door is open so you can steal a look into the courtyard.

The courtyard is known as an Atrium. The atrium has a fountain in the centre. Many Christian teachings would happen in the Atrium and when people were ready, they would be baptized in this area. A person was not allowed enter a Catholic church without being baptized. (So many rules!) It is for this reason that we have fountains in front of churches and famous baptisteries located throughout the country.

When you peer through the street door, you will see that the façade of the church itself is far from early Christian in style. It was redone at some point in the Neo-classical design. If you look to the left of the lightly coloured façade you can catch a glimpse of the original building. But, there is so little exposed that you cannot get any idea of the original design.

Head back up the stairs to sidewalk level, when you turn the corner to enter the building you will enter through an elaborate Baroque-style doorway.

Note:

Most of the churches in Rome are free to enter. Quite often you will see people standing at the doorway with a basket perched at waist level just waiting for your donation to drop into it. It is up to you whether you want to donate to their cause or not, but be sure to know that the money you donate isn’t likely going to the church you are entering.

There is usually someone standing at this door to take your money so you may enter. There is no fee to enter any church in Rome. Don't pay the fee, it is a scam.

The Church of St. Clemente is said to occupy the site of the house of St. Clement, the friend and fellow labourer of St. Paul. The house of St. Clement was used as an oratory by the early Christians and converted into a church about 350 CE.

Legend tells us that Clemente was the author of an Epistle to the Corinthians which was written c. 96 CE to deal with disturbances in the church at Corinth. The letter is one of the earliest witnesses to the authority of the Church of Rome and was so highly regarded that it was read publicly at Corinth with the Scriptures in the second century.

Fourth-century accounts speak of Clemente’s forced labour in the mines during exile to Crimea during the reign of the Emperor Trajan (98-117 CE) and his missionary work there, which prompted the Romans to tie him to an anchor and throw him into the Black Sea. Sometime later, the story tells us that the water receded revealing a tomb built by angels from which his body was recovered. The legend of Clemente’s life and martyrdom are now regarded as fictional, but the story has influenced the artwork in this church. As you are looking at the mosaics, note the anchor that Clemente holds. Anchors at the time of Clemente’s death were trapezoidal in shape, but the anchor depicted in the mosaics is more modern, likely so those viewing the mosaics could recognize Clemente without difficulty.

The old Basilica disappeared in the fire of the Norman adventurer, Robert Guiscard, in 1084, during the sack of Rome. It was rebuilt on the same spot, by Pope Paschal II (1108). Instead of building other foundations, he filled in the ruins of the destroyed Basilica and built the present upper church. He recycled items from the lower church, such as the ciborium (canopy-like structure built over the altar), the choir screens, the ambones (elevated structure from which the readings are proclaimed), and the pillars to use in the new church.

In 1857, workmen who were repairing the foundation of the adjoining convent of the Irish Dominicans, discovered a wall covered with pictures which proved to have belonged to an aisle of the lower church, that had been lost and forgotten for many centuries. Below this wall were buildings of the Republican period, part of a house believed to be the early house and the oratory of St. Clement and also a very well preserved pagan Temple of Mithras. More excavation cleared out the old basilica, bringing to light its original fresco decoration. What to See in Rome, J. Paglia, pages 360-361, 1938 and Wonders of Italy, G. Fattorosso page 423)

The Basilica of Saint Clement (Italian: Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano) was built during the height of the Middle Ages, in 1100. It is a lovely church to visit as it presents 2,000 years of history as you descend the interior steps. It is a Roman Catholic, minor basilica dedicated to Pope Clement I. There is some discrepancy as to whether Clemente was the third or fourth Pope of Rome. However, he held the seat from c. 92 CE to c. 100 CE. Clement was a popular name and altogether there were 14 Pope Clements.

The street view exterior that you see from the sidewalk is rather simple and barn-like with very little decoration. Most early Christian churches followed the practice of exterior-simplicity so non-Christians passing by, would not be aware of the richness within the building. The brickwork is typical Roman and you can see that it has had various modifications over the years. If you descend the exterior steps and peer through the door you will see that the entrance leads into a courtyard. We can’t enter the church by this door, it is always locked, but sometimes the door is open so you can steal a look into the courtyard.

The courtyard is known as an Atrium. The atrium has a fountain in the centre. Many Christian teachings would happen in the Atrium and when people were ready, they would be baptized in this area. A person was not allowed enter a Catholic church without being baptized. (So many rules!) It is for this reason that we have fountains in front of churches and famous baptisteries located throughout the country.

When you peer through the street door, you will see that the façade of the church itself is far from early Christian in style. It was redone at some point in the Neo-classical design. If you look to the left of the lightly coloured façade you can catch a glimpse of the original building. But, there is so little exposed that you cannot get any idea of the original design.

Head back up the stairs to sidewalk level, when you turn the corner to enter the building you will enter through an elaborate Baroque-style doorway.

Note:

Most of the churches in Rome are free to enter. Quite often you will see people standing at the doorway with a basket perched at waist level just waiting for your donation to drop into it. It is up to you whether you want to donate to their cause or not, but be sure to know that the money you donate isn’t likely going to the church you are entering.

The Apse Mosaic

The mosaic in the apse of San Clemente is one of the finest in Rome. What we see today was created in the 12th century, and, with the exception of the crucifix, is based on the original 4th or 5th century design.

On the triumphal-arch wall surrounding the apse, we find St. Lawrence, beardless, with short dark hair, seated on the left in the company of St. Paul, who has a high forehead and long black hair and beard. St. Lawrence has the grill of his martyrdom under his feet. If you look carefully at St. Lawrence’s garments and his delightful slippers, you will see the flames that symbolize his martyrdom. On the right sits St. Peter, the same fellow who is perched on the top of Trajan’s Column. Peter is recognizable because always has short white curly hair and beard. St. Clement is to the right holding his anchor so we now who he is. Below these two fellows are two prophets with scrolls that foretell the coming of the Messiah. Below are images of Jerusalem, the traditional home of the Jews, and on the other side, Bethlehem, the home of the Gentiles.

In the centre at the top, we find the Christ Pantocrator flanked by the four creatures of the Tetramorph. On the underside of the arch, in the centre is the Chi Rho, a symbol originating in Constantine’s vision before the great battle at the Milvian Bridge. Think back to the Arch of Constantine when you think about Milvian Bridge. The Chi Rho looks like an X with a tall letter P through it. In the Greek alphabet X equals chi and P equals rho of the Greek word XPIΣTOΣ which equals Christ.

At the top of the apse is the shell-like decorative device, called a concha, that has its roots in Roman mosaics like the one in the House of Neptune and Amphitrite in the ruins at Herculaneum. At the top of the mosaic is the Hand of God which holds the crown of martyrdom above Christ’s head.

The most remarkable part of the interior is the mosaic decoration of the tribune. The apse is full of stylized grape and acanthus spirals in which we find dozens of birds, animals, objects and tiny human figures which symbolize Christian virtues. The beautifully spiraling vines are probably a reference to Christ’s statement, “I am the true vine, and you are the branches.” Below, across the bottom of the apse, we find a variety of figures and symbols, including a monk feeding chickens and a peacock, the symbol of resurrection and eternal life.

In the centre is a cross on which Christ hangs, surrounded by twelve doves who symbolize the apostles. The cross is surrounded by a vine that seems to have thorns and is perhaps a reference to the legend that tells us that the stems of roses received thorns only after the Crucifixion and the crown of thorns. The cross grows out of a patch of acanthus which symbolizes resurrection, and the four rivers of Paradise that represent the word of God traveling to the four corners of the earth. There are two oil lamps echoing Christ’s statement, “I am the light of the world.” As well, we find two adult deer, drinking the waters of life, and a tiny deer, symbolizing a neophyte, sniffing at a snake that represents evil.

Across the bottom of the apse, are twelve sheep symbolizing the twelve apostles. In the centre is the Pascal Lamb with his halo.

Terms:

Pantocrator: A specific depiction of Christ, with one hand in blessing while holding a book in the other hand.

Tetramorph: A symbolic arrangement of four elements. In Christian art you will see the symbols of the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Matthew is depicted as a man, Mark as a lion, Luke as and ox, and John as an eagle. In this church, we see all four of them. In Santi Cosma and Damiano, where we were earlier, we only saw two of the four, as two had been hidden behind the Baroque wall addition.

On the triumphal-arch wall surrounding the apse, we find St. Lawrence, beardless, with short dark hair, seated on the left in the company of St. Paul, who has a high forehead and long black hair and beard. St. Lawrence has the grill of his martyrdom under his feet. If you look carefully at St. Lawrence’s garments and his delightful slippers, you will see the flames that symbolize his martyrdom. On the right sits St. Peter, the same fellow who is perched on the top of Trajan’s Column. Peter is recognizable because always has short white curly hair and beard. St. Clement is to the right holding his anchor so we now who he is. Below these two fellows are two prophets with scrolls that foretell the coming of the Messiah. Below are images of Jerusalem, the traditional home of the Jews, and on the other side, Bethlehem, the home of the Gentiles.

In the centre at the top, we find the Christ Pantocrator flanked by the four creatures of the Tetramorph. On the underside of the arch, in the centre is the Chi Rho, a symbol originating in Constantine’s vision before the great battle at the Milvian Bridge. Think back to the Arch of Constantine when you think about Milvian Bridge. The Chi Rho looks like an X with a tall letter P through it. In the Greek alphabet X equals chi and P equals rho of the Greek word XPIΣTOΣ which equals Christ.

At the top of the apse is the shell-like decorative device, called a concha, that has its roots in Roman mosaics like the one in the House of Neptune and Amphitrite in the ruins at Herculaneum. At the top of the mosaic is the Hand of God which holds the crown of martyrdom above Christ’s head.

The most remarkable part of the interior is the mosaic decoration of the tribune. The apse is full of stylized grape and acanthus spirals in which we find dozens of birds, animals, objects and tiny human figures which symbolize Christian virtues. The beautifully spiraling vines are probably a reference to Christ’s statement, “I am the true vine, and you are the branches.” Below, across the bottom of the apse, we find a variety of figures and symbols, including a monk feeding chickens and a peacock, the symbol of resurrection and eternal life.

In the centre is a cross on which Christ hangs, surrounded by twelve doves who symbolize the apostles. The cross is surrounded by a vine that seems to have thorns and is perhaps a reference to the legend that tells us that the stems of roses received thorns only after the Crucifixion and the crown of thorns. The cross grows out of a patch of acanthus which symbolizes resurrection, and the four rivers of Paradise that represent the word of God traveling to the four corners of the earth. There are two oil lamps echoing Christ’s statement, “I am the light of the world.” As well, we find two adult deer, drinking the waters of life, and a tiny deer, symbolizing a neophyte, sniffing at a snake that represents evil.

Across the bottom of the apse, are twelve sheep symbolizing the twelve apostles. In the centre is the Pascal Lamb with his halo.

Terms:

Pantocrator: A specific depiction of Christ, with one hand in blessing while holding a book in the other hand.

Tetramorph: A symbolic arrangement of four elements. In Christian art you will see the symbols of the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Matthew is depicted as a man, Mark as a lion, Luke as and ox, and John as an eagle. In this church, we see all four of them. In Santi Cosma and Damiano, where we were earlier, we only saw two of the four, as two had been hidden behind the Baroque wall addition.

The icon of Christ Pantocrator is one of the most widely used religious images of Orthodox Christianity. Generally speaking, in Byzantine church art and architecture, an iconic mosaic or fresco of Christ Pantocrator occupies the space in the central dome of the church, in the half-dome of the apse or on the nave vault.

The San Clemente Pantocrator shows Christ fully frontal with a somewhat melancholy and stern look on his face. His right hand is raised in blessing. His left hand holds a closed book with a richly decorated cover featuring the Seven Seals. Christ is rather Byzantine-looking in this Pantocrator, with his beard, long brown hair which is centrally parted, large brown eyes and long nose. His halo is not solid, but instead, shows a cross, representing Christ Crucified.

The crucifix, from Latin cruci fixus meaning one fixed to a cross, depicts an image of Christ on a black cross standing on a shelf attached to the cross. For some reason the mosaicist let him rest, for eternity, on a shelf allowing a little more gentle depiction to death. Crucifixion was a ghastly and horrific way to cause a slow, painful and humiliating death.

Most crucifixes portray Christ on a Latin cross such as the one in this mosaic, rather than any other shape, such as a Tau cross or a Coptic cross. On a Latin cross the vertical beam is higher than the crossbeam; it looks like a lowercase “t”. A Tau cross looks like an uppercase “T”, where the vertical beam is not higher than the horizontal beam. A Coptic cross incorporates a circle at the top of the cross.

There are 12 white, lovely and detailed doves on the cross which represent the 12 apostles. The virgin Mary stands to His right and St. John the beloved disciple, on His left. Note the rosy cheeks of Mary and John and the lovely shading particularly in John’s robes.

The San Clemente Pantocrator shows Christ fully frontal with a somewhat melancholy and stern look on his face. His right hand is raised in blessing. His left hand holds a closed book with a richly decorated cover featuring the Seven Seals. Christ is rather Byzantine-looking in this Pantocrator, with his beard, long brown hair which is centrally parted, large brown eyes and long nose. His halo is not solid, but instead, shows a cross, representing Christ Crucified.

The crucifix, from Latin cruci fixus meaning one fixed to a cross, depicts an image of Christ on a black cross standing on a shelf attached to the cross. For some reason the mosaicist let him rest, for eternity, on a shelf allowing a little more gentle depiction to death. Crucifixion was a ghastly and horrific way to cause a slow, painful and humiliating death.

Most crucifixes portray Christ on a Latin cross such as the one in this mosaic, rather than any other shape, such as a Tau cross or a Coptic cross. On a Latin cross the vertical beam is higher than the crossbeam; it looks like a lowercase “t”. A Tau cross looks like an uppercase “T”, where the vertical beam is not higher than the horizontal beam. A Coptic cross incorporates a circle at the top of the cross.

There are 12 white, lovely and detailed doves on the cross which represent the 12 apostles. The virgin Mary stands to His right and St. John the beloved disciple, on His left. Note the rosy cheeks of Mary and John and the lovely shading particularly in John’s robes.

Lower Levels

The church is a three-tiered complex of buildings over which archaeologists have minor disagreements as to origin. Nonetheless, all agree that it is a most remarkable complex of history and architecture.

Quick Look:

First Building: The present basilica; the main floor, was built in the year 1100 during the height of the Middle Ages.

Second Building: Beneath the present basilica is a 4th-century basilica that had been converted out of the home of a Roman nobleman, part of which had in the 1st century briefly served as an early church, and the basement of which had in the 2nd century briefly served as a mithraeum. A mithraeum is an adapted natural cave or cavern, or a building imitating a cave. When possible a mithraeum was constructed within or below an existing building.

Third Building: It has long been believed that the home of a Roman nobleman had been built on the foundations of a Republican Era building that had been destroyed in the Great Fire of 64 CE. As more research and study is done, it has been noted that no fire damage is exists in this section; it is now questionable, whether it was destroyed in the fire of 64 or whether the level was just filled in with dirt. Either way, this ancient church was transformed over the centuries from a private home that was the site of clandestine Christian worship in the 1st century to a grand public basilica by the 6th century, reflecting the emerging Catholic Church’s growing legitimacy and power. The archaeological traces of the basilica’s history were discovered in the 1860s by Father Joseph Mullooly, (or M.U. Looly, Paglia, page 362)

A More Detailed Look:

Before the 4th century

The lowest levels of the present basilica contain remnants of the foundation of possibly a Republican Era building that might have been destroyed in the Great Fire of 64. An industrial building, perhaps the Imperial Mint of Rome was built or remodeled on the same site during the Flavian period and shortly thereafter an insula, a kind of apartment building or multi-level house, that provided housing for all but the elite. About a hundred years later (c. 200), the central room of the insula was remodeled for use as part of a mithraeum, that is, as part of a sanctuary of the cult of Mithras. The main cult room (the speleum, cave), which is about 9.6m long and 6m wide, was discovered in 1867 but could not be investigated until 1914 due to lack of drainage. The exedra, a semi-circular recess often crowned with a semi-dome, at the far end of the low vaulted space, was trimmed with pumice to render it more cave-like.

Central to the main room of the sanctuary was an altar, in the shape of a sarcophagus, and with the main cult relief of the tauroctony; which is the central icon of Mithras slaying a bull, on its front face. The torchbearers Cautes and Cautopates appear on the left and right faces of the same monument. A dedicatory inscription identifies the donor as one pater (father) Cnaeus Arrius Claudianus, perhaps of the same clan as Titus Arrius Antoninus’ mother.

Other monuments discovered in the sanctuary include a bust of Sol, kept in the sanctuary in a niche near the entrance, and a figure of Mithras petra generix, Mithras born of the rock.

One of the rooms adjoining the main chamber has two oblong brickwork enclosures, one of which was used as a ritual refuse pit for remnants of the cult meal. All three monuments mentioned above are still on display in the mithraeum.

4th-11th century

At some time in the 4th century, the lower level of the industrial building was filled in with dirt and rubble and its second floor remodeled. An apse was built out over part of the domus, whose lowest floor, along with the Mithraeum, was filled in. This first basilica is known to have existed in 392, when St. Jerome wrote of the church dedicated to St. Clement. The early basilica was the site of councils presided over by Pope Zosimus (417) and Symmachus (499). The last major event that took place in the lower basilica was the election in 1099 of Cardinal Rainerius of St. Clemente as Pope Paschal II.

Interior of the Second Basilica

Apart from those in Santa Maria Antiqua, the largest collection of early medieval wall paintings in Rome is to be found in the lower basilica of San Clemente. Four of the largest frescoes in the basilica were sponsored by a lay couple, Beno de Rapiza and Maria Macellaria, at some time in the last part of the 11th century. The frescoes focus on the life, miracles, and translation of St. Clement, and on the life of St. Alexius.

Beno and Maria are shown in two of the paintings, once on the façade of the basilica together with their children, Altilia and Clemens, offering gifts to St. Clement, and on a pillar on the left side of the nave, where they are portrayed witnessing a miracle performed by St. Clement. Below this last scene, is one of the earliest examples of the passage from Latin to vernacular Italian: a fresco of the pagan Sisinnius and his servants, who think they have captured St. Clement but are dragging a column instead. Sisinnius encourages the servants in Italian “Fili de le pute, traite! Gosmari, Albertel, traite! Falite dereto colo palo, Carvoncelle!”, which, translated into English means: “Come on, you sons of bitches, pull! Come on, Gosmari, Albertello, pull! Carvoncello, give it to him from the back with the pole!” The saint speaks in Latin, in a cross-shaped inscription: “Duritiam cordis vestris, saxa trahere meruistis”, which means “You deserved to drag stones due to the hardness of your hearts.”

The Second Basilica

The current basilica was rebuilt in a campaign by Cardinal Anastasius, 1099-1120. A now outdated hypothesis, held that the original church had burned out during the Norman sack of the city under Robert Guiscard in 1084, but no evidence of fire damage in the lower basilica has been found to date. One possible explanation is that the lower basilica was filled in and the new church built on top due to the close association of the lower structure with the imperial opposition pope (“antipope”) Clement III / Wibert of Ravenna. Today, it is one of the most richly adorned churches in Rome. The ceremonial entrance (a side entrance is ordinarily used today) is through an atrium surrounded by arcades, which now serves as a cloister.

Fronting the atrium is Fontana’s chaste facade, supported on antique columns, and his little campanile. The basilica church behind it is in three naves divided by arcades on ancient marble or granite columns, with Cosmatesque inlaid paving which is a style of inlaid stonework which draws its name from the Cosmati family, who were marble craftsmen of Rome. The 12th-century schola cantorum (Singer’s school) incorporates marble elements from the original basilica. Behind it, in the presbytery is a ciborium, which is a canopy-like structure built over the altar of a Christian church, raised on four gray-violet columns over the shrine of Clement in the crypt below. The episcopal seat stands in the apse, which is covered with mosaics on the theme of the Triumph of the Cross that are a high point of Roman 12th century mosaics.

Irish Dominicans have been the caretakers of San Clemente since 1667, when England outlawed the Irish Catholic Church and expelled the entire clergy. Pope Urban VIII gave them refuge at San Clemente, where they have since remained, running a residence for priests studying and teaching in Rome. The Dominicans themselves conducted the excavations in the 1950s in collaboration with Italian archaeology students.

In one chapel, there is a shrine with the tomb of Saint Cyril of the Saints Cyril and Methodius who created the Glagolitic alphabet, which is the oldest known Slavic alphabet from the 9th century. The verb glagoliti means to speak. These two saints also Christianized the Slavs. Pope John Paul II used to pray there sometimes for Poland and the Slavic countries.

Wikipedia

Who was Robert Guiscard?

Robert Guiscard (c. 1015 – 17 July 1085) was a Norman adventurer conspicuous in the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily. Robert was born into the Hauteville family in Normandy. He went on to become Count of Apulia and Calabria (1057–1059), then Duke of Apulia and Calabria and Duke of Sicily (1059–1085). His brother was the important Roger of Normandy.

He had an overbearing character and a thoroughly villainous mind; he was a brave fighter, very cunning in his assaults on the wealth and power of great men; in achieving his aims absolutely inexorable, diverting criticism by incontrovertible argument. He was a man of immense stature, surpassing even the biggest men; he had a ruddy complexion, fair hair, broad shoulders, eyes that all but shot out sparks of fire. In a well-built man one looks for breadth here and slimness there; in him all was admirably well-proportioned and elegant. Homer remarked of Achilles that when he shouted his hearers had the impression of a multitude in uproar, but Robert’s bellow, so they say, put tens of thousands to flight.

Wikipedia

Terms:

Fresco: A fresco is a painting that was done on wet, freshly laid plaster. The paint is absorbed into the plaster itself. The most famous frescoes are by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel.

Narthex: A narthex is a vestibule, lobby or entrance hall, which stretches across the west end of some early Christian churches. It is usually screened from the nave by a wall, set apart for those teaching the faith.

Rite: A rite is a certain uniform arrangement of words, symbols and ceremonies.

Quick Look:

First Building: The present basilica; the main floor, was built in the year 1100 during the height of the Middle Ages.

Second Building: Beneath the present basilica is a 4th-century basilica that had been converted out of the home of a Roman nobleman, part of which had in the 1st century briefly served as an early church, and the basement of which had in the 2nd century briefly served as a mithraeum. A mithraeum is an adapted natural cave or cavern, or a building imitating a cave. When possible a mithraeum was constructed within or below an existing building.

Third Building: It has long been believed that the home of a Roman nobleman had been built on the foundations of a Republican Era building that had been destroyed in the Great Fire of 64 CE. As more research and study is done, it has been noted that no fire damage is exists in this section; it is now questionable, whether it was destroyed in the fire of 64 or whether the level was just filled in with dirt. Either way, this ancient church was transformed over the centuries from a private home that was the site of clandestine Christian worship in the 1st century to a grand public basilica by the 6th century, reflecting the emerging Catholic Church’s growing legitimacy and power. The archaeological traces of the basilica’s history were discovered in the 1860s by Father Joseph Mullooly, (or M.U. Looly, Paglia, page 362)

A More Detailed Look:

Before the 4th century

The lowest levels of the present basilica contain remnants of the foundation of possibly a Republican Era building that might have been destroyed in the Great Fire of 64. An industrial building, perhaps the Imperial Mint of Rome was built or remodeled on the same site during the Flavian period and shortly thereafter an insula, a kind of apartment building or multi-level house, that provided housing for all but the elite. About a hundred years later (c. 200), the central room of the insula was remodeled for use as part of a mithraeum, that is, as part of a sanctuary of the cult of Mithras. The main cult room (the speleum, cave), which is about 9.6m long and 6m wide, was discovered in 1867 but could not be investigated until 1914 due to lack of drainage. The exedra, a semi-circular recess often crowned with a semi-dome, at the far end of the low vaulted space, was trimmed with pumice to render it more cave-like.

Central to the main room of the sanctuary was an altar, in the shape of a sarcophagus, and with the main cult relief of the tauroctony; which is the central icon of Mithras slaying a bull, on its front face. The torchbearers Cautes and Cautopates appear on the left and right faces of the same monument. A dedicatory inscription identifies the donor as one pater (father) Cnaeus Arrius Claudianus, perhaps of the same clan as Titus Arrius Antoninus’ mother.

Other monuments discovered in the sanctuary include a bust of Sol, kept in the sanctuary in a niche near the entrance, and a figure of Mithras petra generix, Mithras born of the rock.

One of the rooms adjoining the main chamber has two oblong brickwork enclosures, one of which was used as a ritual refuse pit for remnants of the cult meal. All three monuments mentioned above are still on display in the mithraeum.

4th-11th century

At some time in the 4th century, the lower level of the industrial building was filled in with dirt and rubble and its second floor remodeled. An apse was built out over part of the domus, whose lowest floor, along with the Mithraeum, was filled in. This first basilica is known to have existed in 392, when St. Jerome wrote of the church dedicated to St. Clement. The early basilica was the site of councils presided over by Pope Zosimus (417) and Symmachus (499). The last major event that took place in the lower basilica was the election in 1099 of Cardinal Rainerius of St. Clemente as Pope Paschal II.

Interior of the Second Basilica

Apart from those in Santa Maria Antiqua, the largest collection of early medieval wall paintings in Rome is to be found in the lower basilica of San Clemente. Four of the largest frescoes in the basilica were sponsored by a lay couple, Beno de Rapiza and Maria Macellaria, at some time in the last part of the 11th century. The frescoes focus on the life, miracles, and translation of St. Clement, and on the life of St. Alexius.

Beno and Maria are shown in two of the paintings, once on the façade of the basilica together with their children, Altilia and Clemens, offering gifts to St. Clement, and on a pillar on the left side of the nave, where they are portrayed witnessing a miracle performed by St. Clement. Below this last scene, is one of the earliest examples of the passage from Latin to vernacular Italian: a fresco of the pagan Sisinnius and his servants, who think they have captured St. Clement but are dragging a column instead. Sisinnius encourages the servants in Italian “Fili de le pute, traite! Gosmari, Albertel, traite! Falite dereto colo palo, Carvoncelle!”, which, translated into English means: “Come on, you sons of bitches, pull! Come on, Gosmari, Albertello, pull! Carvoncello, give it to him from the back with the pole!” The saint speaks in Latin, in a cross-shaped inscription: “Duritiam cordis vestris, saxa trahere meruistis”, which means “You deserved to drag stones due to the hardness of your hearts.”

The Second Basilica

The current basilica was rebuilt in a campaign by Cardinal Anastasius, 1099-1120. A now outdated hypothesis, held that the original church had burned out during the Norman sack of the city under Robert Guiscard in 1084, but no evidence of fire damage in the lower basilica has been found to date. One possible explanation is that the lower basilica was filled in and the new church built on top due to the close association of the lower structure with the imperial opposition pope (“antipope”) Clement III / Wibert of Ravenna. Today, it is one of the most richly adorned churches in Rome. The ceremonial entrance (a side entrance is ordinarily used today) is through an atrium surrounded by arcades, which now serves as a cloister.

Fronting the atrium is Fontana’s chaste facade, supported on antique columns, and his little campanile. The basilica church behind it is in three naves divided by arcades on ancient marble or granite columns, with Cosmatesque inlaid paving which is a style of inlaid stonework which draws its name from the Cosmati family, who were marble craftsmen of Rome. The 12th-century schola cantorum (Singer’s school) incorporates marble elements from the original basilica. Behind it, in the presbytery is a ciborium, which is a canopy-like structure built over the altar of a Christian church, raised on four gray-violet columns over the shrine of Clement in the crypt below. The episcopal seat stands in the apse, which is covered with mosaics on the theme of the Triumph of the Cross that are a high point of Roman 12th century mosaics.

Irish Dominicans have been the caretakers of San Clemente since 1667, when England outlawed the Irish Catholic Church and expelled the entire clergy. Pope Urban VIII gave them refuge at San Clemente, where they have since remained, running a residence for priests studying and teaching in Rome. The Dominicans themselves conducted the excavations in the 1950s in collaboration with Italian archaeology students.

In one chapel, there is a shrine with the tomb of Saint Cyril of the Saints Cyril and Methodius who created the Glagolitic alphabet, which is the oldest known Slavic alphabet from the 9th century. The verb glagoliti means to speak. These two saints also Christianized the Slavs. Pope John Paul II used to pray there sometimes for Poland and the Slavic countries.

Wikipedia

Who was Robert Guiscard?

Robert Guiscard (c. 1015 – 17 July 1085) was a Norman adventurer conspicuous in the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily. Robert was born into the Hauteville family in Normandy. He went on to become Count of Apulia and Calabria (1057–1059), then Duke of Apulia and Calabria and Duke of Sicily (1059–1085). His brother was the important Roger of Normandy.

He had an overbearing character and a thoroughly villainous mind; he was a brave fighter, very cunning in his assaults on the wealth and power of great men; in achieving his aims absolutely inexorable, diverting criticism by incontrovertible argument. He was a man of immense stature, surpassing even the biggest men; he had a ruddy complexion, fair hair, broad shoulders, eyes that all but shot out sparks of fire. In a well-built man one looks for breadth here and slimness there; in him all was admirably well-proportioned and elegant. Homer remarked of Achilles that when he shouted his hearers had the impression of a multitude in uproar, but Robert’s bellow, so they say, put tens of thousands to flight.

Wikipedia

Terms:

Fresco: A fresco is a painting that was done on wet, freshly laid plaster. The paint is absorbed into the plaster itself. The most famous frescoes are by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel.

Narthex: A narthex is a vestibule, lobby or entrance hall, which stretches across the west end of some early Christian churches. It is usually screened from the nave by a wall, set apart for those teaching the faith.

Rite: A rite is a certain uniform arrangement of words, symbols and ceremonies.

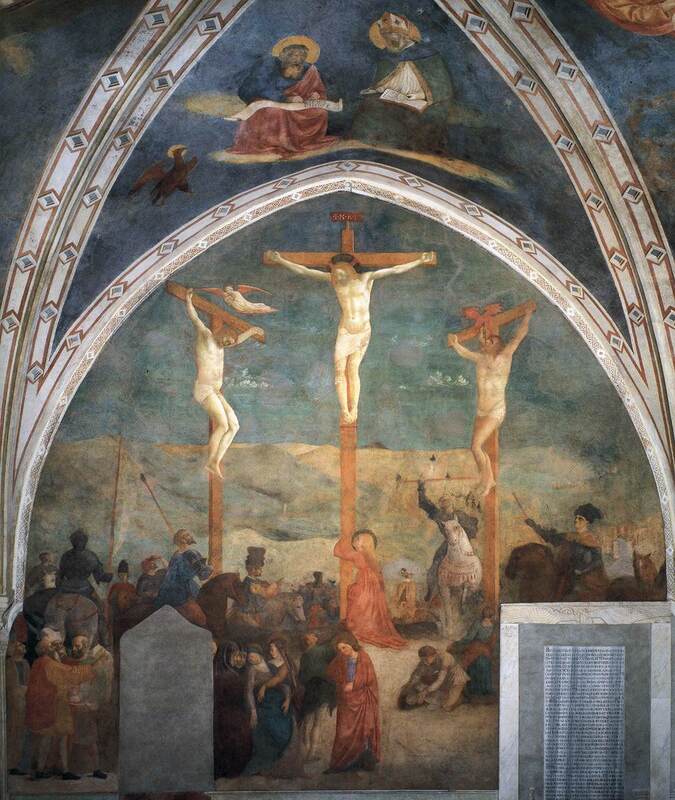

Masolino and St. Catharine

|

Walk over to the left aisle to Branda Castiglione Chapel. It has a closed iron gate in front of it.

This chapel was painted by Masolino da Panicale di Valdelsa, who was known as Little Tom. Masolino was born in 1383, in a commune in the Province of Perugia called Panicale. He is generally considered to be a member of the Florentine school since he joined the Florentine guild Arte dei Medici e Speziali in 1423. There is discussion suggesting that he may have been the first artist to create oil paintings in the 1420s, rather than Jan van Eyck in the 1430s, as was previously supposed.

Masolino was selected by Cardinal Branda Castiglione to paint the Saint Catherine Chapel. Painting began in 1428. This chapel is also known as the Castiglione Chapel, as well as the Chapel of the Sacrament. It is most noted for its eight scenes from the legend of Saint Catharine. Be sure to take a close look at the painting above the arch. It is known as The Annunciation and is most famous.

Masolino was thought to be the teacher of Masaccio, but art historians have recently decided that it might have worked the other way around and that Masaccio was the teacher of Masolino. Masolino was a late Gothic painter of great refinement, elegance and formality. He followed Gothic presentation styles but had learned a lot about perspective. These two fellows worked together with others to produce the magnificent frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, in Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence. (Well worth a trip to Florence to see!)

Masolino was also a very brave painter in the sense that he painted the face of God. Up until this point, we have only seen the right hand of God. This painting displays one of the earliest representations of God the Father that we will find anywhere.

Catherine of Alexandria

There are strong doubts about Catharine’s historical authenticity. Born of a noble family in Alexandria, Egypt, she refused to marry the Emperor Maxentius (Think Milvian Bridge here.) because of her previous “mystic marriage” to Christ. The Emperor ordered fifty Alexandrian philosophers to prove to her the absurdity of her faith, but she effectively countered all their arguments. The Emperor, enraged by this rebuff, ordered that all fifty philosophers be burnt alive and Catharine to be broken on a spiked wheel. The wheel miraculously falls to pieces, and one would think that Catharine would be freed, but she is ultimately beheaded.

The Bible and the Saints, by G. Duchet-Suchaux and M. Pastoureau, 1994, page 76

Link to information regarding the Brand da Castiglione Chapel

This chapel was painted by Masolino da Panicale di Valdelsa, who was known as Little Tom. Masolino was born in 1383, in a commune in the Province of Perugia called Panicale. He is generally considered to be a member of the Florentine school since he joined the Florentine guild Arte dei Medici e Speziali in 1423. There is discussion suggesting that he may have been the first artist to create oil paintings in the 1420s, rather than Jan van Eyck in the 1430s, as was previously supposed.

Masolino was selected by Cardinal Branda Castiglione to paint the Saint Catherine Chapel. Painting began in 1428. This chapel is also known as the Castiglione Chapel, as well as the Chapel of the Sacrament. It is most noted for its eight scenes from the legend of Saint Catharine. Be sure to take a close look at the painting above the arch. It is known as The Annunciation and is most famous.

Masolino was thought to be the teacher of Masaccio, but art historians have recently decided that it might have worked the other way around and that Masaccio was the teacher of Masolino. Masolino was a late Gothic painter of great refinement, elegance and formality. He followed Gothic presentation styles but had learned a lot about perspective. These two fellows worked together with others to produce the magnificent frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, in Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence. (Well worth a trip to Florence to see!)

Masolino was also a very brave painter in the sense that he painted the face of God. Up until this point, we have only seen the right hand of God. This painting displays one of the earliest representations of God the Father that we will find anywhere.

Catherine of Alexandria

There are strong doubts about Catharine’s historical authenticity. Born of a noble family in Alexandria, Egypt, she refused to marry the Emperor Maxentius (Think Milvian Bridge here.) because of her previous “mystic marriage” to Christ. The Emperor ordered fifty Alexandrian philosophers to prove to her the absurdity of her faith, but she effectively countered all their arguments. The Emperor, enraged by this rebuff, ordered that all fifty philosophers be burnt alive and Catharine to be broken on a spiked wheel. The wheel miraculously falls to pieces, and one would think that Catharine would be freed, but she is ultimately beheaded.

The Bible and the Saints, by G. Duchet-Suchaux and M. Pastoureau, 1994, page 76

Link to information regarding the Brand da Castiglione Chapel

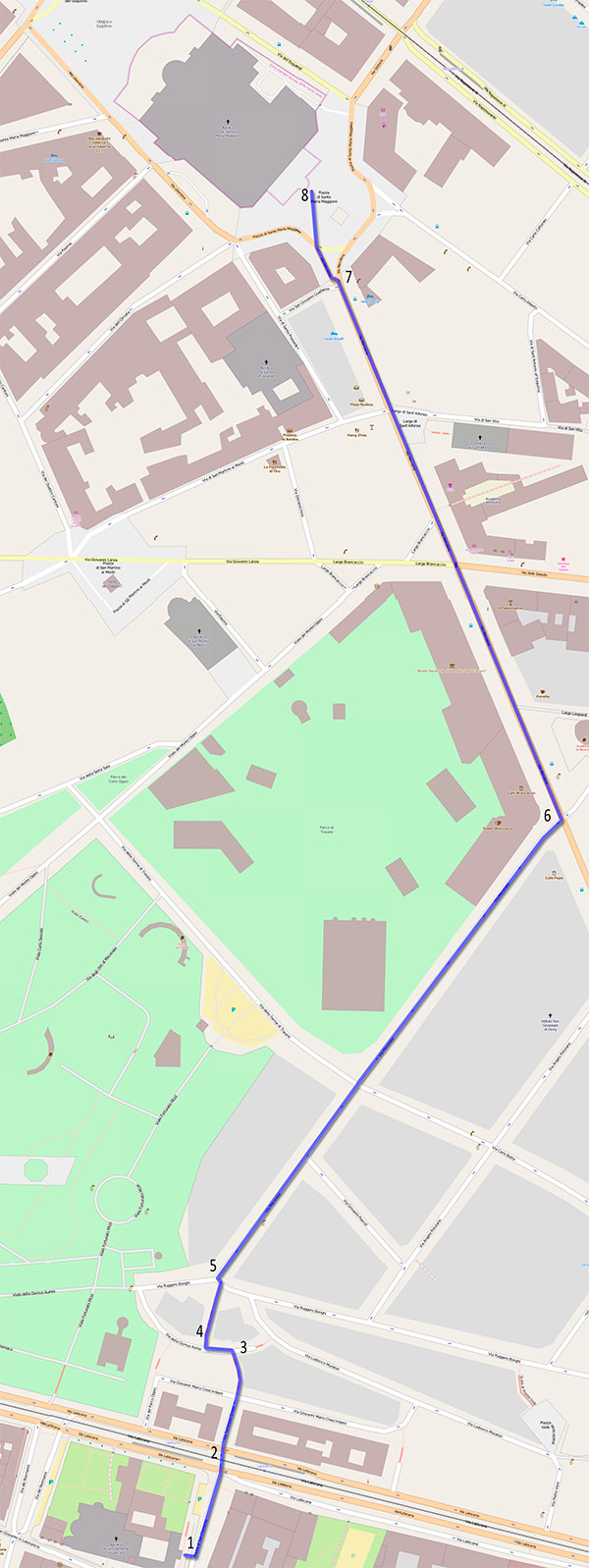

Map: St. Clemente to Santa Maria Maggiore - Distance: 1Km Time to walk: 30 Min

This is a long walk. You might want to stop for a coffee or wine break along the way.

- Turn left as you exit the side door, left at the corner and follow the road to the next corner

- At the intersection cross both one-way versions of Via Labicana onto Via Tommaso Grossi.

- Follow the road to the steps, climb the steps and turn left at Via della Domus Aurea

- make a quick right up another set of steps.

- At the top of the steps, cross Via Ruggero Bonghi and continue on Via Macerate. This is the longest part of the walk, approximately 350 metres. You will cross Via Delle Terme di Traiano.

Turn left at Via Merulana, This is a long walk too. cross Largo Brancaccio. Keep going. Cross Via di San-Martini ai Monti - farther still! - At the end of the bend in the road, the street opens into a piazza. You will see a clock tower and the church a little to the left.